Making us care about murderers

Crime fiction is fast overtaking romance as the biggest selling genre. But what is its appeal?

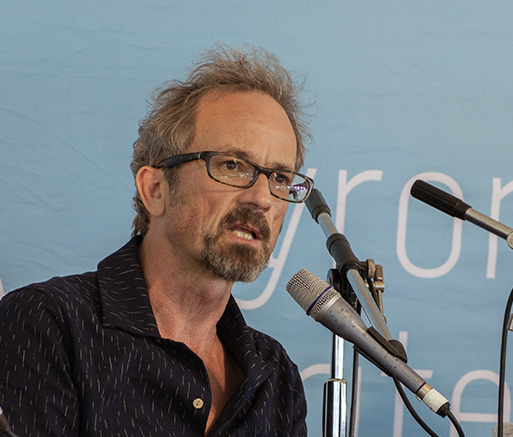

Dervla McTiernan, author of The Ruin, Chris Womersley, author of The Low Road and Bereft, and Candice Fox, a prolific writer who has written 13 books since 2013 and co-writes the Harriet Blue series with James Patterson, came together to talk about why people love crime fiction.

McTiernan likes Sophie Hannah’s thoughts that the crime writer puts the reader’s pleasure before their own, and that, by their nature, the crime fiction plots are tense and suspenseful.

Fox believes that crime writers and readers share an interest ‘but [readers] do not have the time to fit crime into their lives.’

She once spent five hours alone with a serial killer on death row at San Quentin State Prison.

The most common reaction she received from her fans was ‘oh my god, I’m so jealous. I wanted to talk to a serial killer’ but that was universally followed by ‘I can’t do that, I’m a normal person.’

‘There are probably heaps of people who would love to do it,’ she said, ‘but don’t have the excuse.’

Womersley said he is fascinated by what makes people commit the crime.

‘My interest is in people who have been pushed to the edge of their moral boundaries and forced to make a decision,’ he said. The reader ‘always hopes the protagonist will overcome his/her shortcomings, but fear they won’t’.

People who love crime fiction come from all walks of life.

Fox told the story of how, after she had been co-writing with Patterson for a while, she attended a dinner with another of Patterson’s co-writers, Bill Clinton. The former US president.

Clinton badgered her all the way through dinner, wanting inside information on their next novel until she scolded him.

‘Mr President, I can’t tell you that. It’s a spoiler. You’re just going to have to wait.’

The audience rippled with laughter at how the former President of the United States was just like any enthralled fan.

An essential element of successful crime writing is the psychology of the killer mind.

McTiernan said she knows if she has hit the mark because ‘if it doesn’t feel alive on the page to you, it’s not going to come alive for the readers’.

‘I have to start with a character I feel something for, and go from there.’

She added that what she found ‘more shocking was the minutiae’ of a story: it’s the small, mundane details and connections that have the power to shock.

Like when a murder happens because of bureaucratic procedures, everyone has experience of being affected by the bureaucracy, even if they haven’t been impacted by a murder.

In this case, the victim had been killed because the killer had gotten bail because his DNA from two other rapes was caught up in an eight-month backlog at the crime lab.

‘She was killed because of bureaucracy,’ McTiernan said.

In real life, we don’t usually empathise with the killers. But in crime fiction, bad guys – or gals – have to be written as engaging characters and the writer’s task is to make the reader care for them.

‘If you show what people love, it does humanise them,’ Womersley said. Show the reader how similar they are to everyone else.

Fox added ‘most people have experienced the necessary emotions for murder, had been that angry.’ But the vast majority of us have that little voice in their head that says ‘no’.

The discussion then turned to the protagonists – the detective and crime fighters.

Fox related how Patterson gave her some advice when they started co-writing. It was that the setting and the crime don’t matter. What does matter is ‘you have to have characters that people really deeply care about and care about them fast’. You have to do that in the first chapter.

McTiernan said the protagonist in her first book, The Ruin, is a nice guy who had, up to the start of the book, led a comfortable, law-abiding life.

Womersley suggested that she should make him suffer.

McTiernan assured him that ‘that was exactly the plan’.

Jeffery Clark is a Southern Cross University Digital Media and Communications Student.