Stop buying stuff, alright!

With Earth Overshoot Day – 1 August for 2018 – behind us already, we have already used up the total annual amount of natural resources the planet can generate.

Earth Overshoot Day is calculated by dividing the amount of natural resources generated by Earth that year by humanity’s consumption of Earth’s natural resources for that year, and multiplying it by 365.

The first Earth Overshoot Day calculation was made in 1987 and it was found that by December 19, we had consumed more natural resources than was available for the whole year. A twelve-day shortfall.

Roll forward 31 years and Earth Overshoot Day has raced forward to the start of August – a shortfall of 152 days.

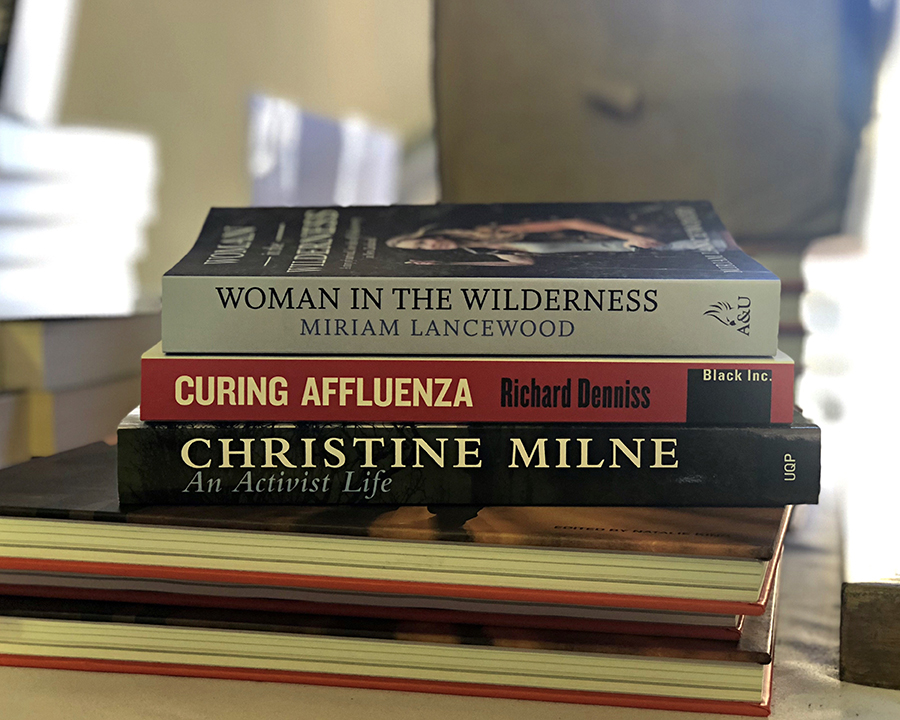

Richard Denniss, economist and writer of Curing Affluenza, Christine Milne, former leader of Australian Greens, and Miriam Lancewood, writer of Woman in the Wilderness, gathered to share their perspectives on how and why we must reduce our consumerism.

Firstly, in the last 30 years, Australians have bought into two lies. The first is we are worse off today than we have been in the previous 50 years.

Denniss argued: ‘Australia is one of the richest countries in the world, and we live in the richest point in world history’, and our gross domestic production (GDP) is comparable to Russia’s.

Our population, 25 million, is even more remarkable as Russia’s population is five times larger than ours.

The second, and logic defying, lie is that wealth can be generated by buying things we do not need, and do not use.

People who lived in the post-war years had learned to buy use only what they needed, not wanted.

As children, Milne said, ‘we only had three sets of clothes, we had the yard clothes, the church clothes, and our school uniform.’

Today, we all have spaces filled with items we do not use and throw out things that still work.

Consumerism, this love of buying, is clogging our world with things we do not want or use, and which we waste.

Instead we need to learn materialism, and ‘love our stuff, again’, Denniss said.

He suggested it would be far better for the economy if we spent money on services, which has a higher flow on effect, instead spending money of things.

Lancewood’s experience of living in the New Zealand wildness taught her how few things we actually need to live.

After resigning their jobs, she and her husband sold everything they had, keeping only what would fit into two backpacks.

Lancewood had a simple rule for choosing clothes to keep: ‘When it’s cold, I put everything on.’ What did not get put on was not kept.

For other items she wore sandals, and socks for winter, a billy, a pan for cooking, matches, a tent, a sleeping bag, a mat, toothbrushes, and a compass.

‘What else would you need?’ she asked.

Amazingly, when they headed off into the New Zealand wilderness, it was with supplies to last the winter. They stayed for seven years.

Meanwhile, Australia has not been as proactive as many European Union countries in reducing waste.

Milne said many EU countries have decided not to open any more landfills or high-temperature incinerators.

‘Anyone selling anything with packaging now has to take back that packaging,’ she said. This extends to tyres, batteries and even pharmacies must take back unused medications.

Denniss reminded everyone that ‘the only thing stopping us from implementing any policies we want, is our insecurities and feeling of lack of power.’

‘Democracy thrives on high expectations, but we’ve been trained to have low expectations.’

Once we rode on the sheep’s back, today we produce very little. Our economy has already gone through massive changes.

Our economy is going to change again and what we do today is simply ‘haggling over the shape and pace of the change,’ to come, Denniss reminded us.

Jeffery Clark is a Southern Cross University Digital Media and Communications Student.