Conversations from Byron

Myth And Folklore in Literature

Listen Now

About the speakers

Sarah Armstrong

Sarah Armstrong

Sarah Armstrong has written five novels – including Salt Rain, shortlisted for the Miles Franklin – and, most recently, two stories for young readers: Big Magic and Magic Awry.

Eliza Henry-Jones

Eliza Henry-Jones

Eliza Henry-Jones is an author based on a small flower farm on Wurundjeri land. She has published five novels, most recently Salt and Skin.

Holly Ringland

Holly Ringland

Holly Ringland is a writer, storyteller, and television presenter. The Seven Skins of Esther Wilding was an instant national bestseller.

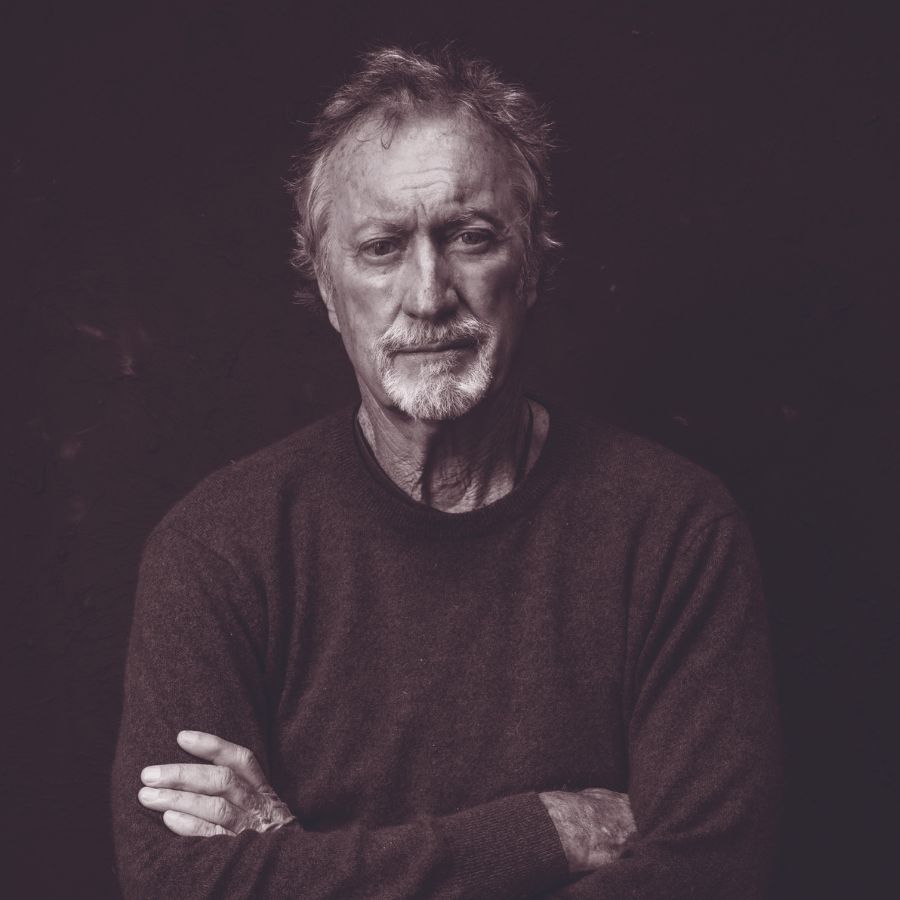

Kári Gíslason

Kári Gíslason

Kári Gíslason is a writer and academic. His latest book, The Sorrow Stone, is an historical novel that reimagines one of the medieval Icelandic sagas.

Donate to our Festival Fund

The exchange of stories and ideas sustains us in challenging times. Now more than ever we are relying on your support to help us continue celebrating Australian stories and literature, enhancing the skills of local writers, and nurturing the next generation of readers and writers. As a not-for-profit organisation run with a small team of staff and volunteers, contributions of any size go a long way in enriching the creative culture of our community. Amounts over $2 are tax deductible. Thank you.

Shirley Le

Shirley Le Myf Warhurst

Myf Warhurst Oliver Phommavanh

Oliver Phommavanh Mandy Nolan

Mandy Nolan

Jacinta Parsons

Jacinta Parsons Tracey Spicer

Tracey Spicer Susan Johnson

Susan Johnson

Bebe Backhouse

Bebe Backhouse Nakkiah Lui

Nakkiah Lui Maxine Beneba Clarke

Maxine Beneba Clarke Cheryl Leavy

Cheryl Leavy

Susan Johnson

Susan Johnson Maggie MacKeller

Maggie MacKeller Peter Polites

Peter Polites Jill Eddington

Jill Eddington

Sandra Thom-Jones

Sandra Thom-Jones Mandy Nolan

Mandy Nolan

Robert Waldinger

Robert Waldinger James Kirby

James Kirby Hilton Koppe

Hilton Koppe David Roland

David Roland

Marele Day

Marele Day

Bryan Brown

Bryan Brown Chris Hanley

Chris Hanley

Evelyn Araluen

Evelyn Araluen Daniel Browning

Daniel Browning

Hannah Kent

Hannah Kent Susan Wyndham

Susan Wyndham

Trent Dalton

Trent Dalton David Leser

David Leser

Dylin Hardcastle

Dylin Hardcastle Kathryn Heyman

Kathryn Heyman Jess Hill

Jess Hill Gina Rushton

Gina Rushton

Yves Rees

Yves Rees Mariam Veiszadeh

Mariam Veiszadeh

Judy Atkinson

Judy Atkinson Paul Callaghan

Paul Callaghan Marcia Langton

Marcia Langton Cheryl Leavy

Cheryl Leavy

Van Badham

Van Badham Tim Burrows

Tim Burrows Ed Coper

Ed Coper Margaret Simons

Margaret Simons

A.C. Grayling

A.C. Grayling Mia Thom

Mia Thom Damon Gameau

Damon Gameau Anne-Marie Te Whiu

Anne-Marie Te Whiu Luka Lesson

Luka Lesson

Bronwyn Adcock

Bronwyn Adcock Joëlle Gergis

Joëlle Gergis Gabrielle Chan

Gabrielle Chan

Saul Griffith

Saul Griffith Tim Hollo

Tim Hollo Sarah Wilson

Sarah Wilson

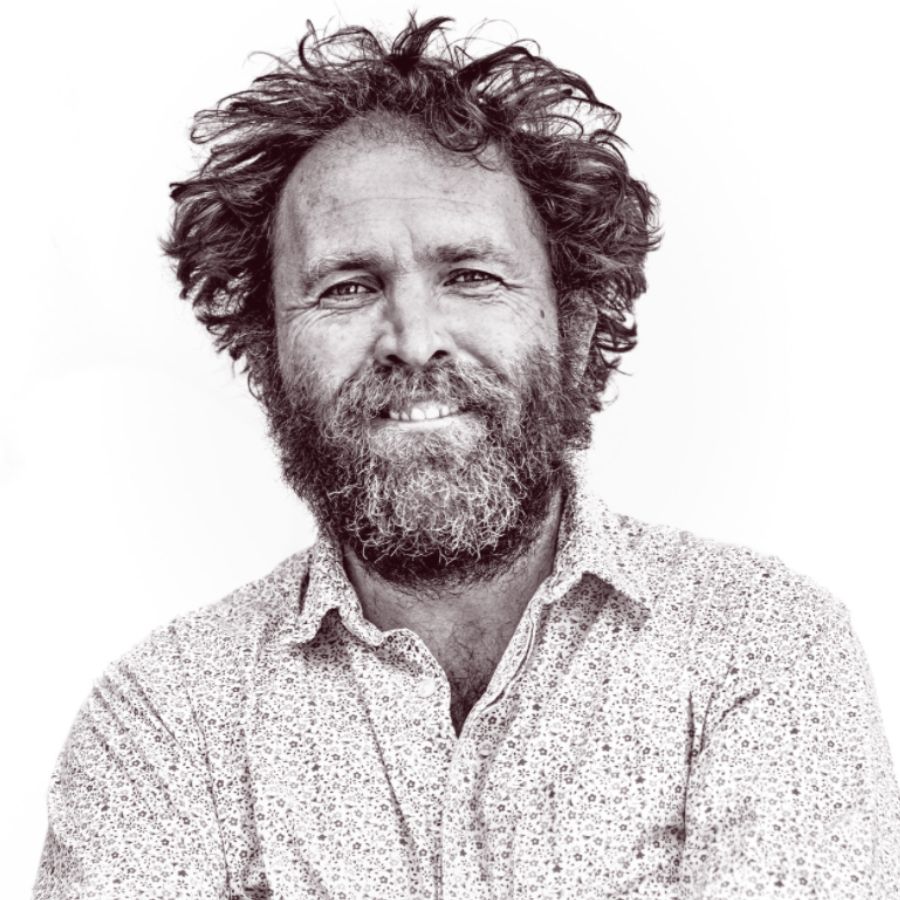

Tim Baker

Tim Baker Chloe Hooper

Chloe Hooper Nikki Gemmell

Nikki Gemmell