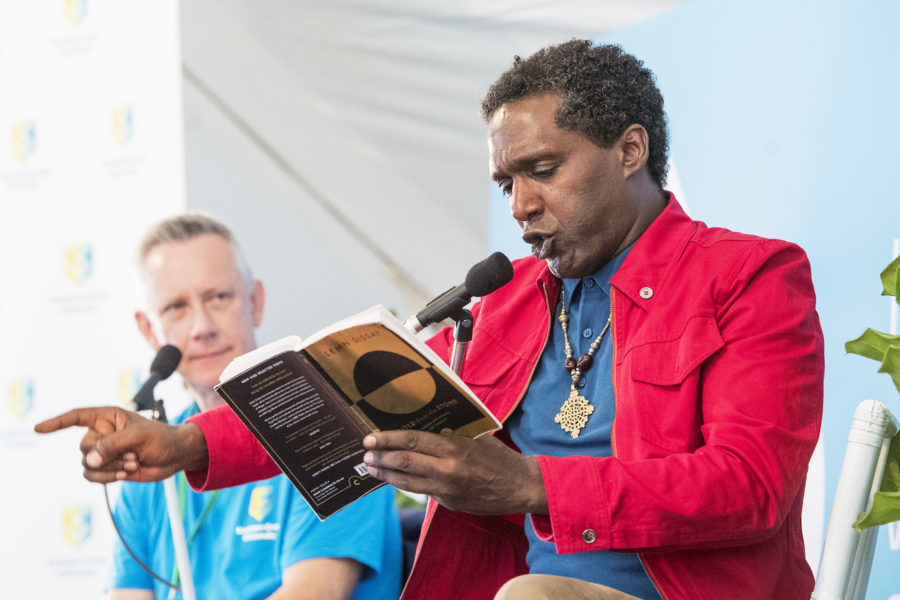

Poetry over politics: Lemn Sissay

Poetry is not a ‘minority sport,’ says Lemn Sissay. And if you’ve ever had the honour of hearing Sissay perform, you would agree with his proposition that ‘poetry is everything’.

Well, perhaps not everything. When session chair Southern Cross University Vice Chancellor Adam Shoemaker suggests that ‘it’s not about length, it’s about depth and breadth,’ Sissay didn’t miss a beat, ‘Are we still talking about poetry?’

Sissay had a traumatic childhood. He thought his name was Norman Mark Greenwood until he was 18: ‘Mark, after Mark from the Bible.’

However, he declares, ‘I am not defined by my scars, but my incredible ability to heal.’

His story speaks to the prejudice at the heart of society’s mistreatment of children whose experience falls outside mainstream ideals, notwithstanding that these ideals are foregrounded in the lie of the perfect family.

‘Disfunction is at the heart of all functional families,’ he says.

When Sissay’s Ethiopian mother found herself pregnant in England while studying abroad, she asked the State for help. Although, instead of complying with her wish, which was to foster her baby while she completed her studies, they conspired to adopt him to an English family.

However, his English family abandoned him to institutionalised ‘care’ at age 12, when they deemed his adolescent behaviour to be evidence of the devil inside.

Society’s need to judge, and particularly to judge disempowered women, is ‘the beginning of stealing children’, says Sissay. ‘We are responsible … we’re so damn sanctimonious.’

When commissioned to write a poem for the 2012 London Olympics, Sissay was toured around the Olympic site, and found a matchmaking factory in its vicinity.

He discovered the story of the factory’s female workers, who staged the first documented worker’s strike in the United Kingdom in 1888, and the spark was lit!

His beautiful poem, Spark Catchers, attracted global attention over 100 years after Annie Besant published an article lamenting, in Sissay’s words, ‘if only there was a poet …. to speak for these women’.

Sissay is proud of his achievements – he was elected as the Chancellor of the University of Manchester after being encouraged to run by the Student Union, and was subsequently awarded an Honorary Doctorate for service to the arts (the administrative process began before his rapid rise within the echelons of university power).

As Chancellor, convention would dictate that he present the Honorary Doctorate to himself so author Jeanette Winterson took his place on the podium.

The symbolism of being awarded by a fellow writer and poet who, like Sissay, endured incredible hardship as a child at the hands of a society who deemed to judge them as lesser than, was an ‘incredibly special thing’.

‘These children deserve respect for what and who they are,’ he says, ‘and respect in the delivery of service’.

Has the system changed?, an audience member asks.

‘Yes and no … change doesn’t matter if there are people still being abused,’ he laments.

As chancellor, he is proud that The University of Manchester has ‘social responsibility as a central goal’. Session chair Adam Shoemaker, himself vice-chancellor of Southern Cross University, nodded in agreement.

Despite the challenges of his upbringing, Sissay sees himself as ‘lucky’. He sees the value of his experience in the opportunity to connect with others.

‘We have the opportunity to build bridges,’ he says in a sentiment that echos from yesterday’s session with North Korean defector Hyeonseo Lee.

‘I take my signs where I can get them, ’ Sissay says. The signs from his unprecedented rise to university chancellor, defeating former politician Lord Peter Mandelson for the role along the way, were pretty clear: poetry trumps politics.

Sissay muses that if aliens arrived on earth, they would discover far more about the human condition from the poets than the politicians.

‘We need to see poetry for how big it is,’ he says. And with Lemn Sissay and a microphone, how can we not?

Rebecca Sargeant is a Southern Cross University Creative Writing student.